The Basics:

- For ages 8 and up

- For 1 to 4 players

- Approximately 20 minutes to complete

Geek Skills:

- Counting & Math

- Logical & Critical Decision Making

- Reading

- Risk vs. Reward

- Visuospatial Skills

- Hand/Resource Management

Learning Curve:

- Child – Easy

- Adult – Easy

Theme & Narrative:

- Raid a randomly generated dungeon

Endorsements:

- Gamer Geek mixed!

- Parent Geek mixed!

- Child Geek approved!

Overview

Exploring dungeons takes time and work. You have to get your party in order, gear up, and then make sure everyone is set to arrive at the dungeon’s precipice at the same time. It’s a lot like trying to get the kids up, fed, and out to school. Huh… Anyway, in this game, you can put aside all that prepping nonsense and jump right into dungeons deep. Deal a few cards and drop some cubes. BOOM! Instant dungeon! But like all raids into dark places full of nasty beasts, you’ll have to have your wits about you and some luck to spend!

Dungeon Drop, designed by Scott R. Smith and published by Gamewright Games, is comprised of 87 cubes (in various sizes and colors), 15 Race cards, 10 Class cards, 10 Quest cards, six custom dice, four meeples, four Teamwork tokens, four player aids, four solo tokens, four turn order markers, and one score tracker. The cards are as thick and as durable as your standard playing card, and the dice and cubes are made of solid plastic. The entire game fits in a small box, which is also in the shape of a cube.

Game Set Up

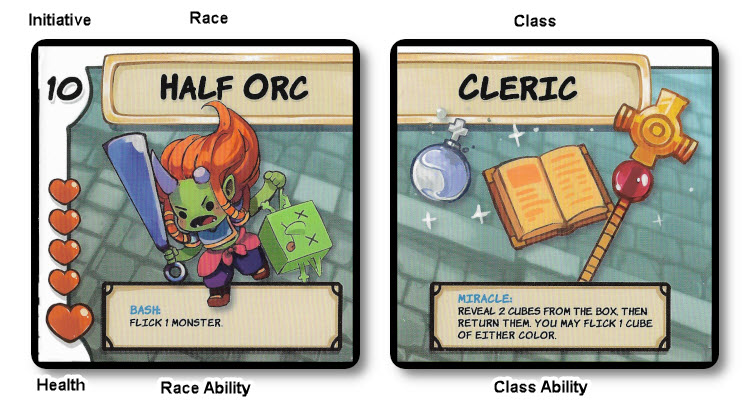

To set up the game, first shuffle the Race and Class cards separately. Then deal one Race and one Class card to each player at random. These cards should be placed face-up in front of their owning player. The result will be a unique race and class the player gets to control during the game. This combination of the two cards is referred to as the player’s “Hero.”

Second, give each player their turn order marker according to their Hero’s initiative value. The Hero with the lowest initiative value is given the “1” turn order marker, followed by the second-lowest receiving the “2” turn order marker, and so on.

Third, shuffle the Quest cards and deal one to each player, face-down. The player should look at their unique Quest, but keep it hidden until it’s later revealed. Quest cards will determine how each player scores dice in the game, as well as indicating any special scoring bonuses. Note that Quest cards are not created equal. There are a few that are considerably more difficult. For example, a popular comparison is the “Earl’s Errand” and the “Collector’s Curiosity” Quests. Due to how the game is played, the “Collector’s Curiosity” Quest is significantly more difficult to leverage for a possible victory. This should not be considered a stain upon the game, however, and there is an easy way to help players pick the right quest that is within reach. See “House Rules” for a possible solution.

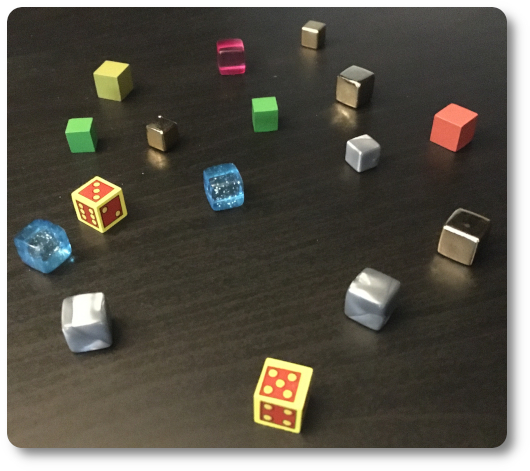

Fourth, separate all the small cubes from the larger ones, making two piles. Take the red “Dragon” cube and add it to the pool of smaller cubes. The player with the Hero with the lowest initiative now takes the small cubes and the Dragon cubes into their hands and drops them about six inches off the table. The drop should result in an even spread of the cubes without more than one or two cubes touching each other.

Fifth, take the remaining larger cubes and place them in the bottom of the game box.

That’s it for the game set up. Time to explore the dungeon!

Dropping into the Dungeon

Dungeon Drop is played in turns and rounds with a set number of three rounds per game. On a player’s turn, they will take the following steps in the sequential order shown here.

Step One: Explore

The player blindly draws a specific number of cubes from the game box. The number of cubes drawn is based on the number of players in the game. For example, if playing with two players, six cubes are drawn, but if playing with four players, only three cubes are drawn. Once the cubes are drawn, the player drops them to the table using the same method as the initial cubes dropped during the game set up.

Example of an active dungeon

Step Two: Take Action

The player may now either activate their Race ability or their Class ability, but not both. The ability selected will instruct the player to either take immediate action or provide a bonus for the turn.

Step Three: Loot

The player now forms a “Room” by selecting three grey “Pillar” cubes, drawing a line connecting the three with their eyes. The player should point to the three Pillar cubes they are using, but not touch them. This is helpful for the rest of the players to determine if what the player does next is legal.

After forming the Room, the player carefully collects each cube that is contained within the Room’s boundaries. When collecting, the player removes each cube and places it behind their Hero. Before doing so, they should ensure that the Room they are defining does not contain any “Pillar” cubes, and raiding the room would not result in the Hero expiring (Health dropped to zero or less). If either of these cases is observed, the player must create a different Room.

Step Four: Resolve Exploration

The cubes collected are now resolved.

Treasure cubes are collected in the player’s “Stash,” which is a small pile of cubes placed under the Hero card. Treasures include the following:

- Health Potions: Remove from Stash to recover one Health

- Magic Shield: Remove from Stash to ignore Health loss from one Monster cube

- Gold: Score one point

- Key: Opens a chest

- Chest: Roll the Chest die if paired with one Key cube

- Gems: Variable score values based on the player’s Quest card

Monster cubes are collected but are placed on the player’s Race card, covering the “Heart” icons that represent Health. Monsters include the following:

- Goblin: Reduce Hero’s Health by one and score one point

- Troll: Reduce the Hero’s Health by two and score two points

- Dragon: Reduce the Hero’s Health by eight and score eight points

Heroes do not “die” in this game. Lack of Hero Health means less flexibility in Room raiding. Remember, if your Hero cannot survive raiding a Room, they cannot enter it to begin with.

Step Five: End Turn

After the player has resolved their cubes, their turn is over. To indicate they are done, they take their turn order marker and flip it over. The next player in the round now takes their turn using the same steps previously indicated.

Ending the Round and Counting Treasure

After the last player in the round completes their turn, each player counts the total Weight of the Treasure cubes they have in their stash. This does include Monster cubes. The player with the fewest Treasure cubes is considered the lightest and is given the lowest turn order marker for the next round. The player with the second lightest is given the next lowest turn order marker and so on. Thematically speaking, the more treasure you have, the heavier you are, resulting in a slower Hero who is hindered by their success.

Leaving the Dungeon

After the third round of gameplay has been completed (skipping the end of the round’s new turn order action), the game comes to an end. The following is now completed in the order provided:

- Reveal Quest Cards: Each player now reveals their Quest card and reads it out loud.

- Open Chests: Separate and pair one Key cube with one Chest cube. Roll each of the paired Chest die. The rolled value indicates the score of the chest provided. Set these rolled values to one side. Any unpaired Key and Chest cubes are ignored.

- Total Your Treasure: Using the rules set on the player’s Quest card and the value of the treasure by default, determine the score earned via the player’s collected Treasure cubes. Add to that value the rolled values from the opened Chest cubes. The total amount is the player’s final score.

The winner of the game is the player with the highest score. If there is a tie, the Hero with the highest starting Initiative wins. Which, honestly, doesn’t seem fair.

Game Variants

In addition to the basic game rules previously described, Dungeon Drop has several other methods of play, which are summarized here.

Teamwork

Give each player a matching colored meeple and Teamwork token. Place the Teamwork tokens by the scorecard. During the player’s turn, they may relocate their meeple anywhere in the dungeon area at any time before the currently active player forms their Room. When the Room is looted, any meeples contained within or touching the looted Room is removed and awards the owner one point on the scorecard. At the end of the currently active player’s turn, any meeples still in the Dungeon are returned to the owning player without scoring any points. At the end of the game, the players add the points earned on the scorecard to their final score.

Additional Dungeon Goodies

As of this review, you can visit the Dungeon Drop webpage hosted by Phase Shift Games and download three extras for the game. The first are rules to play solo if you are jonesing to dig deep into a dungeon but are a party of one. The second is a series of short alternative rules that can be added that introduces Hero drafting, Hero constructing, Dungeon constructing, Hero rescuing, rules to remove all dexterity elements to the gameplay (referred to as “Controlled Choas”), and team versus team play. The third is a rather large file that is described as a “toolkit.” It contains images that can be used to create your own rules of the game, including new Hero, Class, and Quest cards.

House Rules

The Quest cards are meant to be dealt randomly to each player. Since a Quest card does not determine if a player wins or not, don’t spend a lot of time hemming and hawing over the difficulty of some quests. The game is simply too light and quick to warrant spending any negative emotional energy on. But if you and your fellow gamers are looking to resolve what might be considered an unfair advantage due to random outcomes, we suggest the following solution. When setting up the game, deal two Quest cards to each player and place the undealt Quest cards out of the game. Each player now looks at their Quest cards, picks one to keep, and passes the other to the player on their left. Now each player takes another look at their two Quest cards and chooses one to put into play and discards the other. This solution does two things. First, it gives players a choice. Second, it gives the players some information they could leverage against one of their opponents.

To learn more about Dungeon Drop, visit the game’s webpage.

Final Word

The Child Geeks had a lot of fun with Dungeon Drop. They liked how they had interesting mixes of races and classes and how the game was never, ever the same no matter how many times they played it. According to one Child Geek, “The game is fast, and you always get a new dungeon to explore. I don’t think I’m really exploring a dungeon when I play. I like to think of it as a giant battleground.” The game is reasonably abstract, especially when it comes to the “walls” and “rooms” of the dungeon, which are always invisible. Another Child Geek said, “Some of the Quests are harder than others, but you can win just by thinking about your rooms carefully.” When all the games were over and the last dungeon put back in the box, the Child Geeks gave Dungeon Drop their full approval.

The Child Geeks had a lot of fun with Dungeon Drop. They liked how they had interesting mixes of races and classes and how the game was never, ever the same no matter how many times they played it. According to one Child Geek, “The game is fast, and you always get a new dungeon to explore. I don’t think I’m really exploring a dungeon when I play. I like to think of it as a giant battleground.” The game is reasonably abstract, especially when it comes to the “walls” and “rooms” of the dungeon, which are always invisible. Another Child Geek said, “Some of the Quests are harder than others, but you can win just by thinking about your rooms carefully.” When all the games were over and the last dungeon put back in the box, the Child Geeks gave Dungeon Drop their full approval.

The Parent Geeks enjoyed the game with their Child Geeks, but their fondness waned when they played with their peer group. According to one Parent Geek, “Great game for the family. I love talking through the possibilities my kids are making and watching them critically consider all their choices. Couldn’t be more pleased with this as a quick and thoughtful family game.” Another Parent Geek said, “Solid game for the fam, but when I played it with adults, the game was somewhat forgotten. I mean, we played it, but we didn’t feel that we were engaged by it as strongly as I do when I play with my family.” When the final monster was slain, and heroes left the darkness of the deep, the Parent Geeks gave Dungeon Drop a mixed level of approval.

The Parent Geeks enjoyed the game with their Child Geeks, but their fondness waned when they played with their peer group. According to one Parent Geek, “Great game for the family. I love talking through the possibilities my kids are making and watching them critically consider all their choices. Couldn’t be more pleased with this as a quick and thoughtful family game.” Another Parent Geek said, “Solid game for the fam, but when I played it with adults, the game was somewhat forgotten. I mean, we played it, but we didn’t feel that we were engaged by it as strongly as I do when I play with my family.” When the final monster was slain, and heroes left the darkness of the deep, the Parent Geeks gave Dungeon Drop a mixed level of approval.

The Gamer Geeks found Dungeon Drop to be a unique game, but found the abstract nature of the game to be fiddly. According to one Gamer Geek, “I like the creativity put into designing this game and how simple parts are being used in a way I have never seen. The game itself is light, but I found the choices I need to make to be a bit too abstract at times. We had a few disagreements, for example, where a room’s dimensions did or did not impact a cube or two. I think this game would be great as a filler at best.” Another Gamer Geek said, “I think this game is random and unruly. Too many outcomes based on luck and randomness to be fun. I might as well be flipping a coin to determine if I win or not.” When the Gamer Geeks slew the dragon, they felt their efforts resulted in a game that some enjoyed, and some did not.

The Gamer Geeks found Dungeon Drop to be a unique game, but found the abstract nature of the game to be fiddly. According to one Gamer Geek, “I like the creativity put into designing this game and how simple parts are being used in a way I have never seen. The game itself is light, but I found the choices I need to make to be a bit too abstract at times. We had a few disagreements, for example, where a room’s dimensions did or did not impact a cube or two. I think this game would be great as a filler at best.” Another Gamer Geek said, “I think this game is random and unruly. Too many outcomes based on luck and randomness to be fun. I might as well be flipping a coin to determine if I win or not.” When the Gamer Geeks slew the dragon, they felt their efforts resulted in a game that some enjoyed, and some did not.

This is a light and fast game. It’s not meant to be taken seriously, but it should be played thoughtfully. I liken it to a more strategic game of Pick Up Sticks, which is the very definition of a “nonsense game.” Unlike the stick version, Dungeon Drop requires the player to think about space, risk, reward, and area using imaginary lines that create a triangle. Everything within that triangle becomes the player’s boon or bane. As the dungeon becomes less dense, the triangles have to start getting bigger with diminishing returns. The result is a game that continues to feed itself but also forces the players to manage their intake. For such a light game meant to be played quickly, it made me pause and reflect several times. Indeed, some of our players even felt “stuck” with their choices, being asked to perform a “damned if I do and a damaged if I don’t” scenario.

This is a light and fast game. It’s not meant to be taken seriously, but it should be played thoughtfully. I liken it to a more strategic game of Pick Up Sticks, which is the very definition of a “nonsense game.” Unlike the stick version, Dungeon Drop requires the player to think about space, risk, reward, and area using imaginary lines that create a triangle. Everything within that triangle becomes the player’s boon or bane. As the dungeon becomes less dense, the triangles have to start getting bigger with diminishing returns. The result is a game that continues to feed itself but also forces the players to manage their intake. For such a light game meant to be played quickly, it made me pause and reflect several times. Indeed, some of our players even felt “stuck” with their choices, being asked to perform a “damned if I do and a damaged if I don’t” scenario.

And herein lies the crux of what tips a player to like or dislike this game based on what I observed. The game gives a player choice, but not control. They are forced to choose but are free to define the outcome that is hardly ever entirely satisfactory. This was seen by some as nothing more than the nature of the game and believed by others to be a limiting factor to the fun they have. It comes down to what type of game you enjoy playing. If you are looking for a level of engagement that requires players to think creatively, then this is your kind of game. If you are looking for a game where strategy and tactics can be leverage to outwit and outplay your opponent, Dungeon Drop isn’t your bag, baby.

Of value to note that this game teaches players – harshly – that dungeon delving is a dangerous endeavor. Many times during the game, players will need to evaluate how much pain their Hero will be receiving when they are drawing the room borders in their mind. In some cases, a player might not be able to survive their turn due to the lack of Health they have to spare and the density of monsters in the dungeon. To me, this was part of the game’s charm. To others, this was found to be a limiting factor that reduces a player’s ability to stay in the game. Several times, players got up from their seats and looked at the dungeon from different angles. Excellent problem solving and a real challenge at times.

I rather enjoyed myself with this game. It was meant to be played quickly with a group who just want to spend some quality time with each other, leaning over a randomly generated abstract dungeon, and challenge each other to think – figuratively speaking – out of the box because you have to think in triangles here. A unique game that pleased many, but didn’t satisfy all. Needless to say, it will be welcomed back at my table. Give it a drop to see if it is a welcomed guest at yours.

This game was given to Father Geek as a review copy. Father Geek was not paid, bribed, wined, dined, or threatened in vain hopes of influencing this review. Such is the statuesque and legendary integrity of Father Geek.