The Basics:

The Basics:

- Ages 5 and Up

- For 2 to 5 players

- About 15 to 20 minutes to complete

Geek Skills:

- Memorization & Pattern Matching

- Risk vs. Reward

Learning Curve:

- Child – Moderate

- Adult – Easy

Theme & Narrative:

- None

Endorsements:

- Gamer Geek rejected!

- Parent Geek approved!

- Child Geek approved!

Overview

I first saw this game at the Australian Games Expo in Canberra in January 2010, and purchased it on the advice of a demonstrator at the Rio Grande Games booth. (I feel obliged to buy at least one children’s game whenever I attend a gaming convention.) Several months later, we continue to play this regularly: a push-your-luck filler game in which it helps to have a good memory!

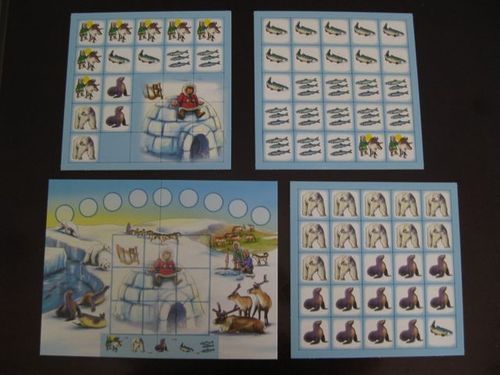

Enuk, designed by Stefan Dorra and Manfredi Reindl, published by Queen Games, includes 74 cardboard tiles, including animal tiles (humans, polar bears, seals, salmon and herring) as well as nine tiles that make up a picture of an Eskimo sitting on an igloo. Set-up is simple: all tiles are placed face-down on the playing surface and “shuffled” (that’s how we do it, anyway, what mah-jong players would call “washing the tiles”).

On his turn, a player turns tiles face-up until the exposed tiles include animals that are adjacent on the food chain. When this happens, any tiles showing prey will “run away” from their predators (i.e., will be turned face down again), and the player removes the remaining face-up tiles to his scoring pile. For example, if a player turns up two polar bears and then two salmon, nothing happens at that point, but if he then turns up a seal, the salmon run away from the seal and the seal runs away from the polar bears. Alternatively, a player may choose to end his turn early rather than risk this occurring.

Finally, if a player exposes a picture tile, his turn ends and he places a meeple (an eskimeeple, I suppose) on the board to indicate that he has a stake in the final phase of the game. He moves all face-up animals to his scoring pile.

After eight reindeer tiles have been exposed (there is a time track to record this), the game moves into the final phase. Players with stakes in this phase declare the identify of a tile before exposing it. If he is correct, he keeps the tile and his turn continues, otherwise it is removed from play and his turn ends. When this phase is completed, the player with the most tiles wins. This can be judged by counting stacks, or (because the cardboard tiles are reasonably and uniformly thick) by comparing the height of the stacks.

Final Word

Memory plays a greater role during the earlier phase of the game rather than the final phase; once you’ve exposed a seal, for example, it is strategically sound to turn up any other tiles you already know to be seals, and to avoid any other tiles you know to be polar bears. The final phase is meant to reward good memory also. In our experience, though, almost all known tiles have been taken by this stage, so it’s mostly blind guessing.

As in Duck, Duck, Bruce!, we often pass comment on the wisdom of ending one’s turn early. My son often states authoritatively, “I wouldn’t do that [draw another tile] if I were you,” as though aware of the precise probability of an unfavorable outcome. That, of course, is one of the major joys of playing games: the interaction between players.