Please Take Note: This is a review of the final game, but it might change slightly based on the success of the Kickstarter campaign. The game is being reviewed on the components and the rules provided with the understanding that “what you see is not what you might get” when the game is published. If you like what you read and want to learn more, we encourage you to visit the game’s website or visit the Kickstarter campaign. Now that we have all that disclaimer junk out of the way, on with the review.

The Basics:

- For ages 4 and up

- For 2 to 5 players

- Approximately 30 minutes to complete

Geek Skills:

- Active Listening & Communication

- Counting & Math

- Logical & Critical Decision Making

- Reading

- Strategy & Tactics

- Risk vs. Reward

- Cooperative & Team Play

- Imagination

Learning Curve:

- Child – Easy

- Adult – Easy

Theme & Narrative:

- Big adventure for little heroes

Endorsements:

- Gamer geek rejected!

- Parent geek approved!

- Child Geek approved!

Overview

German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst, Erik Erikson, said “The playing adult steps side-ward into another reality; the playing child advances forward to new stages of mastery.” Role-playing games challenge people to create concrete solutions from abstract ideas. Imagination in such games is an invaluable tool. Children have an incredible imagination, and now thanks to this game, they have an opportunity to explore new worlds with their family.

Heroes and Treasure, designed by Jason Davis and his daughter (how cool is that?), will reportedly be comprised of 1 Quest Master’s rule book, 1 Campaign booklet (with 10 unique dungeon levels to explore), 11 custom six-sided dice, 12 double-sided map tiles (representing dungeon rooms and corridors), a deck of unspecified number of reference cards (to help keep track of character classes and monsters), 4 Character cards, 13 Monster cards, 80 Life counters, 40 Plastic card stands (representing monsters and heroes), and an unspecified number of additional tokens that are meant to represent the various things one would expect to find in dungeons. For example, doors and treasure chests. As this is a review of an unpublished game, I cannot comment on the game component quality. Xin Ye, who you might know from the Erfworld web comic, provides visual representations of everything in the game, helping all players (regardless of age) imagine the adventure they are in.

Characters and Classes

Heroes and Treasure is set in a high-fantasy world. For those of you who might not know what that means, think Lord of the Rings and you’ve got the general idea. Lots of magic, sword play, heroics, and nasty things that tend to cause trouble. The game is designed for each player to have one character and one player to act as the Quest Master (running the show), but the game system itself lends itself easily for one player to control more than one. This allows the game to be played with as few as two individuals. One controlling the story and the other controlling the adventuring party.

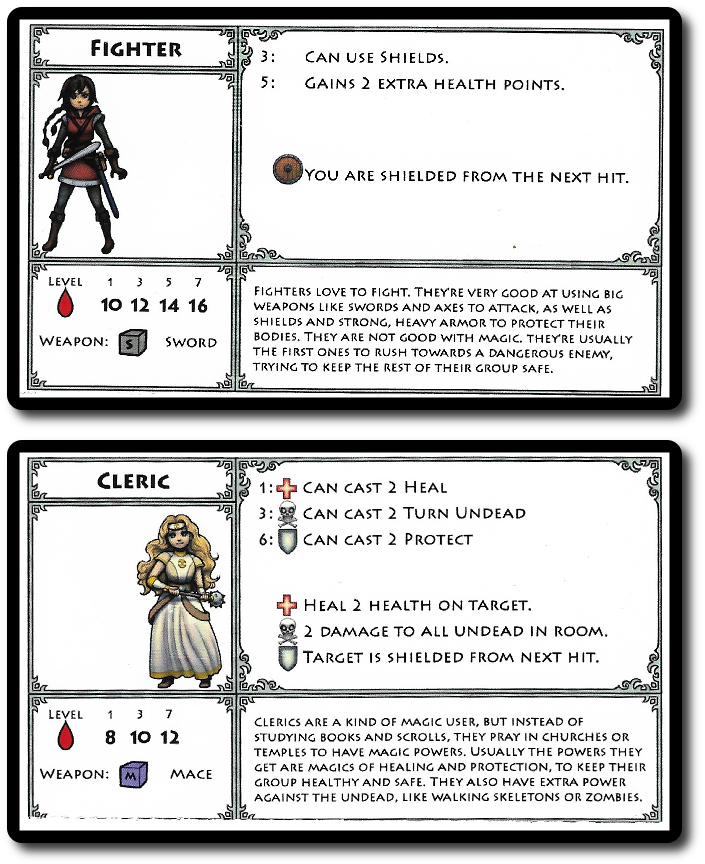

The hero classes are exactly what you would expect in a high-fantasy game. Fighters who fight, Wizards who cast spells, Clerics who heal, and Rogues that steal. Each class has their own special ability which is represented by the custom dice in the game. Each die is six-sided, but the number values are not equal. For example, the Fighter uses the die with different number values than the Cleric. Each class also has specific armor and weapon set restrictions. For those who are familiar with role-playing games, no surprises here. The simplistic approach, however, makes it very obvious for new and inexperience players what characters can and cannot do, not because they are weak or strong, but because it makes sense. This is further reinforced by the roles of the classes, making each unique and specialized.

Dice are represented by both color and by a letter, making it easy for players to quickly understand what die their character needs to roll. For example, the “D” dice is orange. All dice have at least one “pip” on them, but depending on the die type, it will have a different number of blank sides and a different range of possible number values to roll. Blanks represent misses, while those sides with pips represent damage dealt, with each “pip” indicating a hit of one damage.

Weapons, Armor, and Spells

Weapons are considered anything you can use to attack an enemy. This not only includes swords and axes, but also spells. Each weapon is represented with exactly one die most of the time. Therefore, if a player is adventuring in a dungeon with a character that is wielding two swords (one in each hand), they would represent that with two dice. Powerful weapons can also be represented by more than one die, signifying their strength. Weapons can also trigger special effects when used properly.

There is a startling lack of armor in the game, but this should not suggest that characters and monsters are wandering around unprotected. Combat (as described later in this review) is very straightforward. Armor, in most cases, adds an additional level of calculation and complexity by reducing number values rolled. Characters can get shields and other items that reduce damage, but armor itself is not represented as actual pieces to be worn. This is not to say a player cannot find a piece of armor in the game and put it on, changing their stats. This is a role-playing game, after all. However, with just the base rules and default character builds, armor is not so much a thing to be worn, but is rather little more than a noted bonus that adjusts damage taken.

Spells, as suggested, are like weapons. They can do damage, but also more. Spells can heal and when the players become more advanced, can be used like tools. Levitating players over traps and other fun uses to solve interesting problems in the dungeon.

Combat

Combat in the game is fast and purposely kept light. Each character rolls their die and each die roll represents one attack (or hit). The amount of damage inflicted is equal to the number of “pips” on the die value rolled. A blank indicates a miss. If any attack does more than one “pip” of damage, it’s considered a “critical hit”. Each damage dealt reduces the Health Points of the target being attacked. When the target’s Health Points reach zero, they are considered defeated. Once defeated, they are removed from the dungeon. If a character is defeated, the players can decide to continue their adventure or restart the adventure.

Heroes always go first in combat, giving players an opportunity to quickly tackle the situation. The turn order of the heroes is based on class.

- Rogues go first, because they are quick and sneaky

- Warriors go next, because they like to rush in

- Wizard are a bit more cautious and attack when the enemy is clearly distracted by the Warrior and Rogue

- Clerics go last, preferring to take action after they see what their friends can accomplish

Your standard adventuring party will include one of each character class, but players can customize their adventuring party if they so like. If there are more than one class of the same type, the players decide the order in which those classes take their turn when their class normally would.

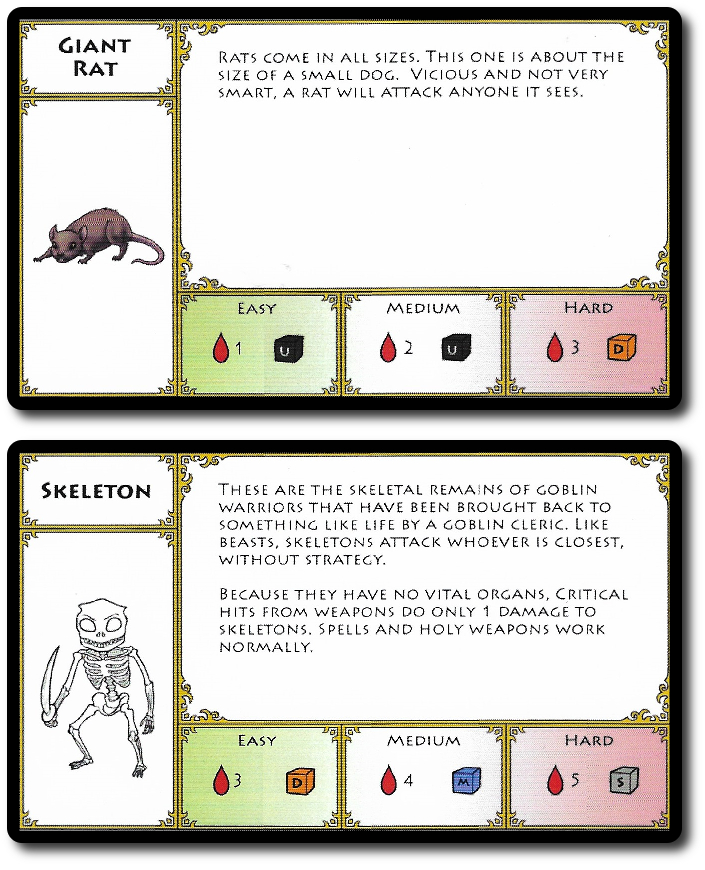

Monsters in the game have a combat order, too. Monsters who have higher Health Points go first, followed by the second highest, and so on. Thematically speaking, the bigger, tougher, and meaner monsters jump into combat before the weaker and more timid monsters. When was the last time you saw a giant rat jump in front of a dragon screaming, “I GOT THIS, LIZARD!”. Never, that’s when.

When it’s the player’s turn to engage in combat (be it a hero or a monster), they do so by completing combat actions. Only one action per turn is possible. The actions are as follows.

- Attack nearest target

- Cast a spell (by spending a spell token)

- Move (up to three spaces using adjacent, non-diagonal movement on the dungeon tiles)

- Use items (like drinking a potion)

- Equip a shield (but only if you are a Warrior)

Certain attacks and spells can introduce a modifier. For example, if a character goes invisible, they are immune to attacks until they attack. Characters can be frozen or stunned, resulting in them not being able to take any action at all.

Hero and Monster Advancement

All heroes start the game as Level One. This not only represents the heroes overall experience level, but also determines what special skill unique to their class they have access to. For example, the Level One Wizard can cast the Frost Bolt that does some damage, but at Level Six, they can the mighty Fireball which ruins just about any enemy’s day. Characters and classes are pre-constructed. Just hand a card to a player and off you go. Health Points are tracked by using counters and weapons and spells are tracked by using dice. A hero “levels up” when they go into the next dungeon. Therefor, a campaign of four dungeons would mean a hero would, at minimum, advance to level four.

Monsters do not “level up”, but they do have “levels of difficulty”. Each monster can be described as either “Easy”, “Medium”, or “Hard” when it comes to their overall difficulty to take down. The different levels of difficulty are noted on the card representing the monster. This makes is super easy to represent a small group of monster of the same type with one being the “mini boss” (that is to say, “Hard” difficulty) and the others being the weaker counter-parts. The starting difficulty value can be adjusted as needed, but the standard rule-of-thumb suggests that the size of the adventuring party and their level should modify the difficulty of the monsters so as to provide a challenge. The goal, after all, is to make each game fun and exciting, not difficulty and stressful. Just enough challenge to make the outcomes of actions unknown, but the decision needed to be made clear as day.

The Dungeon

The dungeons the players will be exploring are represented by tiles. Each dungeon level is described in the books that accompany the game with a map and visual layout of how the dungeon should be built. Some rooms in the dungeon have special rules, which are noted in detail. Dungeon tiles have letters, making it easy for the player setting up the dungeon to find the right tile and the right side of the tile to use. Certain “sets” have certain numbers, making it even easier for players to quickly find the right tile and use the tiles together that make the most sense.

The preferred method of building the dungeon is to layout the tile when the players move into it. This makes the dungeon “open up” as the players explore it rather than being an empty map that the players can already see. Since each dungeon is fairly small, it takes little effort to build the dungeons on the fly.

Item tokens are used to represent things found in the dungeon. Chests and fountains, for example. Doors are used to help with the transition from one dungeon tile to another, but can be locked and even trapped. Fountains, chests, and pits are things that players can interact with. Some might be harmful to the heroes. For example, falling into pit would reduce Health Points.

There are also wandering monsters. Newly discovered rooms in the dungeon could randomly have a wandering monster or two populate it. This also includes previously cleared dungeon rooms, making it possible that an empty room behind the heroes could later be filled with more monsters to tackle. A wandering monster only appears on certain dice rolls. Only rooms have wandering monsters. Corridors remain clear by default. However, the individual running the game is not restricted by this suggestion.

The Campaign and One-Shots

The provided campaign serves as a good introduction to role-playing and makes use of your standard low-level adventures. There’s a mystery to be solved, danger to be faced, and treasure to be won. As the heroes go up in level, so too do the monsters and the difficulty of the dungeon. More traps to avoid, puzzles to ponder, and monsters to battle. All very balanced and well-crafted.

There are no one-shot (single-play) games to be had, but the campaign can be easily broken up if needed. Creating your own dungeon and adventure is a simple task. The game system is light enough to allow the player to design their own with little more than a story in mind. Using the dungeon tiles to help set the stage is a lot of fun when designing your own adventure. When you are done, populate it with the counters, create your map, and then define what each room contains.

Customization is possible, but there are no rules provided that help the player make new monsters. This means balance will be an issue, but the game system itself was designed to keep things as balanced as possible. Stronger monsters use better dice and have more Health Points. Traps and puzzles have outcomes based on what a player does or rolls. While there are no “tools” provided to the player, what is available is easy to use to roll your own adventure or two.

To learn more about Heroes and Treasure, visit the game’s website or visit the Kickstarter campaign.

Final Word

The Child Geeks enjoyed the game, finding the rules to be easy to follow and the adventure a fun one to experience. Combat was quick and it was always clear to the Child Geeks who should do what. According to one Child Geek, “I like how the character cards show you what your character can do so I was never confused about how I could help.” There are plenty of things to reference in the game, reducing downtime that would otherwise be consumed with looking up rules and possible counters. The game wants players to play it, not jump away from the action to go determine the outcome of an event based on five or more variables. Another Child Geek said, “I’ve played more complicated role-playing games and I think this one is OK. Pretty simple, but it was fun.” For those players who already knew how to role-play, Heroes and Treasure was a simpler version of what they were already enjoyed. Not dumbed down, just lighter in weight. In the end, all of our players enjoyed it and fully approved it.

The Child Geeks enjoyed the game, finding the rules to be easy to follow and the adventure a fun one to experience. Combat was quick and it was always clear to the Child Geeks who should do what. According to one Child Geek, “I like how the character cards show you what your character can do so I was never confused about how I could help.” There are plenty of things to reference in the game, reducing downtime that would otherwise be consumed with looking up rules and possible counters. The game wants players to play it, not jump away from the action to go determine the outcome of an event based on five or more variables. Another Child Geek said, “I’ve played more complicated role-playing games and I think this one is OK. Pretty simple, but it was fun.” For those players who already knew how to role-play, Heroes and Treasure was a simpler version of what they were already enjoyed. Not dumbed down, just lighter in weight. In the end, all of our players enjoyed it and fully approved it.

The Parent Geeks also enjoyed it, finding the game to be easy to set up, visually appealing, and fun to play with the family. According to one Parent Geek, “I always knew about role-playing, but never thought I would play it with my kids. So many rules to follow. This game kept things simple and fun. I’d play this again tomorrow if I had the chance.” Another Parent Geek said, “Easy rules and the game system empowers the players. A great way to introduce role-playing to new players and young players!” A number of our Parent Geeks would consider themselves “role-playing veterans”. They found the game system to be very simple and would have poo-poo’ed it if it weren’t for the fact that the very same game system made it possible for them to enjoy a big adventure with their favorite little geeks. The end result was full approval.

The Parent Geeks also enjoyed it, finding the game to be easy to set up, visually appealing, and fun to play with the family. According to one Parent Geek, “I always knew about role-playing, but never thought I would play it with my kids. So many rules to follow. This game kept things simple and fun. I’d play this again tomorrow if I had the chance.” Another Parent Geek said, “Easy rules and the game system empowers the players. A great way to introduce role-playing to new players and young players!” A number of our Parent Geeks would consider themselves “role-playing veterans”. They found the game system to be very simple and would have poo-poo’ed it if it weren’t for the fact that the very same game system made it possible for them to enjoy a big adventure with their favorite little geeks. The end result was full approval.

The Gamer Geeks played the game and rolled their eyes. According to one Gamer Geek, “There is nothing wrong with this role-playing game, but I wouldn’t call it a role-playing system. There is no role-playing. Just simple rules. This is not a role-playing game. It’s a board game. Which is fine. It’s just not for me.” Another Gamer Geek said, “For what it is and who it is intended for, I give it two-thumbs way up. I think it is great the industry is creating traditionally complicated games for younger players. I approve it for the kids, but not gaming elitists.” None of the Gamer Geeks found fault with Heroes and Treasure, but none of them endorsed it, either. As one Gamer Geek put it, “I approve it for the Parent and Child Geeks. Not for the Gamer Geeks.” And that is exactly how the vote resulted.

The Gamer Geeks played the game and rolled their eyes. According to one Gamer Geek, “There is nothing wrong with this role-playing game, but I wouldn’t call it a role-playing system. There is no role-playing. Just simple rules. This is not a role-playing game. It’s a board game. Which is fine. It’s just not for me.” Another Gamer Geek said, “For what it is and who it is intended for, I give it two-thumbs way up. I think it is great the industry is creating traditionally complicated games for younger players. I approve it for the kids, but not gaming elitists.” None of the Gamer Geeks found fault with Heroes and Treasure, but none of them endorsed it, either. As one Gamer Geek put it, “I approve it for the Parent and Child Geeks. Not for the Gamer Geeks.” And that is exactly how the vote resulted.

The designer claims that Heroes and Treasure can be played by someone as young as four. Technically, sure, why not. I found the perfect age to be between ages eight and ten. Old enough to make their own decisions, but not experienced enough to find this role-playing system too simple to be enjoyable. To one of the Gamer Geek’s comments, Heroes and Treasure feels more like a board game than a role-playing game, but I would argue that’s not based on the game itself. You can certainly role-play and the advancement of the heroes feels just like leveling up any other role-playing character. I think it better to suggest that Heroes and Treasure has role-playing elements which is perfect. It mixes the concrete with the abstract.

The designer claims that Heroes and Treasure can be played by someone as young as four. Technically, sure, why not. I found the perfect age to be between ages eight and ten. Old enough to make their own decisions, but not experienced enough to find this role-playing system too simple to be enjoyable. To one of the Gamer Geek’s comments, Heroes and Treasure feels more like a board game than a role-playing game, but I would argue that’s not based on the game itself. You can certainly role-play and the advancement of the heroes feels just like leveling up any other role-playing character. I think it better to suggest that Heroes and Treasure has role-playing elements which is perfect. It mixes the concrete with the abstract.

It’s this mixing of the two, the game played in the mind and the one played on the table, that makes Heroes and Treasure popular with our players. The adventure unfolds in front while the depth of the story unfolds in the imagination. This made it easy to introduce the game, play it with people who don’t know a thing about role-playing games, and have a great time. In fact, I seldom used the term “role-playing”, due to people having plenty of misconceptions. When the games were over I was often asked “This was role-playing? I thought it would be different!” It’s a form of role-playing, to be sure, but the end result was always positive with the right group. And who is that group? Families.

If you are looking to take your loved ones on an adventure through dark dungeons, do give Heroes and Treasure a try. It’s a fun intro to big adventure.

This is a paid for review of the game’s final prototype. Although our time and focus was financially compensated, our words are our own. We’d need at least 10 million dollars before we started saying what other people wanted. Such is the statuesque and legendary integrity of Father Geek which cannot be bought except by those who own their own private islands and small countries.