The Basics:

- For ages 8 and up (publisher suggests 12+)

- For 2 players

- Approximately 120 minutes to complete

Geek Skills:

- Active Listening & Communication

- Counting & Math

- Logical & Critical Decision Making

- Reading

- Memorization

- Strategy & Tactics

- Risk vs. Reward

- Hand/Resource Management

- Bluffing and Misdirection

- Area Control

Learning Curve:

- Child – Moderate

- Adult – Easy

Theme & Narrative:

- Lead your armies and fight to control the Roman Empire

Endorsements:

- Gamer Geek approved!

- Parent Geek approved!

- Child Geek mixed!

Overview

Before the Roman Empire was establish, Caesar waged war against Pompey in hopes of obtaining both military and political superiority. Pompey fought to maintain the status quo, while Caesar fought for change. The countryside erupted into a civil war that lasted for years. Historically, Caesar won, but in this game the players get to decide the fate of the Roman Empire.

Julius Caesar, designed by Grant Dalgliesh, Justin Thompson, and published by Columbia Games, is comprised of 63 wooden Army blocks (31 tan, 31 green, and 1 blue), 27 cards (20 Command, 7 Event), 4 standard six-sided dice, and 1 mapboard. The cards are as thick and durable as your standard playing card. The mapboard is stiff cardstock and unfolds when in play. The blocks are thick and very durable.

On the Eve of War

To set up the game, first place the mapboard between the two players. Players should be facing each other on opposite sides of the playing area.

Second, determine which player will take on the role of Caesar or Pompey (I suggest you let new and inexperienced players command Pompey’s forces). Depending on which historical figure the players select (or are left with), they will take specific Army blocks. There are two ways to initially place the Armies. The first is placing specific Army blocks on specific locations on the mapboard that match historical events. The second is to place the Armies where noted, but then allow the players to swap out certain Army blocks for those of their choosing. In any case, the number of Army blocks per player on the mapboard never exceed the initial setup value. When Army blocks are placed, they are turned so the values are facing the owning player. The blocks should also be rotated so the highest number value is at the top. Any Army blocks in the player’s Levy (a pool of unused Army blocks) should also remain turned away from the opponent.

Third, shuffle the Command and Event cards together to create the draw deck. Place the draw deck to one side of the mapboard. Place the dice next to the draw deck at this time, as well.

That’s it for game set up. Time to forge an empire.

Inspecting the Soldiers and Battlefield

While I do not consider Julius Caesar to be an overly difficult game, it does have a lot of rules that give the players a great deal of flexibility in the game. So much, in fact, that it’s difficult to teach all the game has to offer until certain situations arise. For example, shore combat. That’s really only something that comes into play when a player decides to risk one of their boats.

While our goal is always to educate, I will only summarize the components and game play here with the understanding that I am not covering everything in detail. Again, this is not a difficult game to play or to learn. It’s just too much game to fully document in a review. Also, I’m lazy.

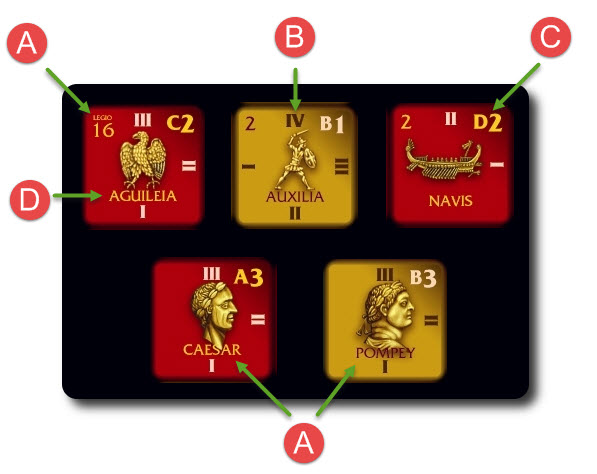

Army Blocks

Army blocks represent different fighting forces, support and siege weaponry, and even important leaders. Army blocks are moved on the mapboard to different locations and initially start the game in different cities. The following information is listed on the Army blocks, but not all Army blocks will list all the information summarized here.

A) Name and Identification Number: Some Army blocks have an identification number that can be used to help keep track of where forces are going to. Some Army blocks also have a name above the identification. The name can also be found below the Army block icon.

B) Strength: The strength of an Army block is similar to its overall health. Army blocks starts at full health, which is later reduced when they are engaged in combat. Strength of an Army block is tracked by rotating it so the next lowest number value is on top. Strength also determines how many dice are rolled by the player when they use the Army block in combat.

C) Combat Rating: The combat rating of an Army block determines its initiative. Initial order is determined by the letter, with “A” going before “B”, and so on with ties going to the defender. The number value indicates the Army block’s firepower, which determines the maximum die roll value that will score a hit.

D) Levy Location: Some Army blocks (specifically, Legions) will display a name of a city that can be found on the mapboard. This indicates the Army block’s levy location. This city is where the Army block is deployed from the Levy pool.

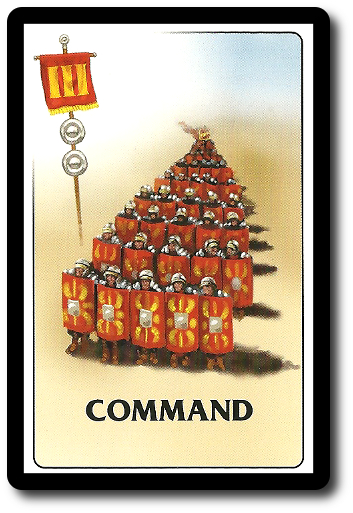

Command and Event Cards

Command cards define how many Moves and Levies the player has for the game turn, in addition to establishing the player turn order. Players are never forced to take the full Move and Levy values noted on their played cards, but nor can they take more than what is listed. Moves and levies not used are lost.

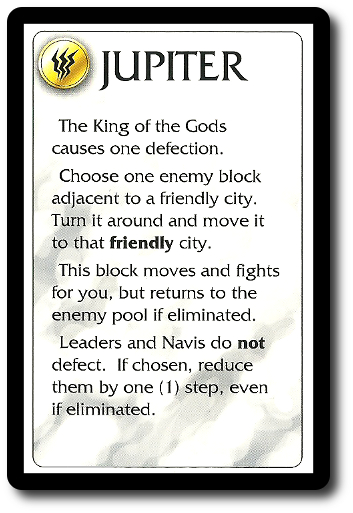

Event cards depict the Roman deities and bend the rules of the game. In truth, the Event cards give the player a one time ability that can be used to gain the upper hand. Not win the battle, mind you, as that is still up to fate. Event cards tip the scales ever so gently in a player’s favor, but never fully. Many players also consider the Event cards something of a cheat, as they can mess with a player’s strategy and tactics.

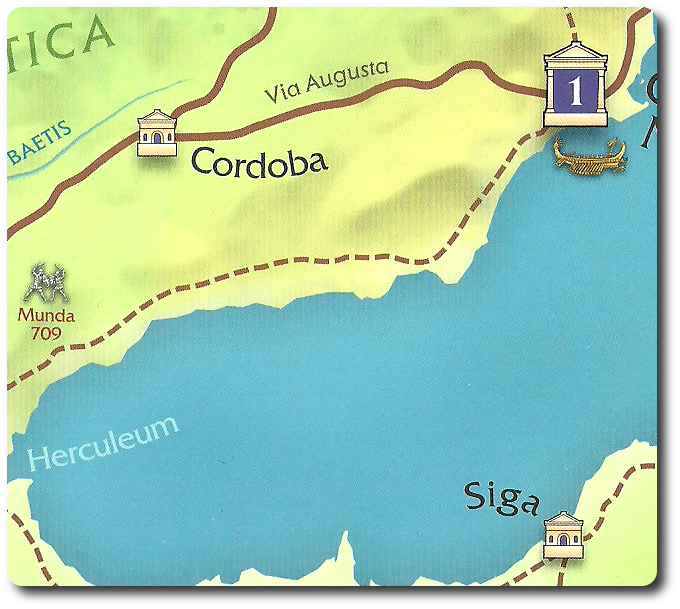

The Mapboard

The mapboard represents the Mediterranean Sea and its surrounding territories. It’s here that the players will lead their armies and engaged one-another. All Army blocks must be located in a city or a sea location, with the “Navis” Army block only able to travel between port cities. City locations have a number value that indicate how many victory points it’s worth. The number value also indicates how many additional armies it can house during the winter. Roads connect cities and territories. Some roads have names (which are listed only for historical purposes). All roads are either “major” (solid line) or “minor” (dotted line), with their designation determining the number of Army blocks that can travel on it during a single turn.

The open waters on the mapboard includes seas, islands, port cities, and even straits. Army blocks can traverse the straits without assistance, but will require “Navis” Army blocks to ferry troops and equipment to different islands or to quickly move from one port city to another.

The Future of Rome

The mapboard depicts the Roman Empire during the time period the game is set in (49-45 BC). The players are not required to use all of the mapboard, but can spread their forces to the far frontier or keep them centrally located in the inner and oldest most portions of the empire. It’s fully up to the player to determine where best to send their troops to meet their strategic and tactical goals.

Julius Caesar is played in 5 rounds (representing years) and each round includes 5 game turns. Each turn is comprised of 3 sequential phases which are summarized here. Before starting a new round (year), deal each player 6 cards. These cards represent commands, marching orders, and abilities the player will make use of during the round. Cards should remain hidden from opponents until played.

Phase 1: Play One Card

From the cards the player has left in their hand, they must now select 1 to play, placing it face-down in front of them. When both players have placed a card, they are simultaneously revealed. Based on the card values, the following is takes place.

If Command Cards Are Played…

- The player with the highest Move value goes first for the turn.

- If both cards have equal Move values, then the player acting as Caesar goes first.

If Event Cards Are Played…

- The player who reveals an Event card goes first for the turn.

- If both cards revealed are Event cards, the game turn immediately ends!

Phase 2: Command

The first player for their turn now resolves the Event card they played or takes their Move and then Levy actions. When completed, the second player takes their Move and then Levy actions.

Movement

Movement in the game is done along routes on roads and sea lanes. Players move groups of 1 or more Army blocks in one city location to another connected city location via one of the two routes. Army blocks can move up to 1 or 2 city locations away from their starting position or up to 2 sea lanes. Army blocks cannot attack an opposing force after moving and cannot enter a city location or fortify an area if they have moved 2 times this turn. The conditions of the roads will also determine how many Army blocks can be moved.

Both the cities and the sea can be contested, changing how the game is played, including movement. The possible status of the cities and the sea are as follows:

- Friendly: location is occupied by 1 or more of the player’s Army blocks

- Enemy: location is friendly towards your opponent

- Vacant: location is neutral towards both players

- Contested: location contains 1 or more of both players’ Army blocks

It’s possible to “pin” an opponent in a location by moving opposing Army blocks into an already occupied position. If the defender of that position wants to move Army blocks out, they must leave an equal number of Army blocks, but are free to move and even attack with the other Army blocks. The only other restriction is that “unpinned” Army blocks cannot travel on roads or the sea used this turn by their opponent. At the same time, a defending player can move in additional troops to further defend and reinforce their Army blocks.

Levy

After all movement is completed, a player can use their Levy value on their card to complete the following in any order.

- Increase the strength value of any Army blocks currently in play by +1

- Bring 1 Army block in the Levy pool into play by placing it in a city location with a strength value of “1”

Phase 3: Battle

After both players have had an opportunity to position their armies, reinforce positions, and bring new units into play, it’s time to battle for superiority.

Battles are only fought between opposing forces located in the same city location or sea location. The order in which these battle are fought is up to the first player. Army blocks that moved into an already occupied location are considered the “attackers”, while the other player is the “defender”.

This is where initiative comes into play. Starting with “A”, then “B”, and so on until all Army blocks have an opportunity to engage in combat. Army blocks remain hidden from the opponent until used in combat. When they are used, they are rotated so the face of the Army block is visible to the opponent (perhaps for the first time in the game). The defender always goes before the attacker.

The player takes a number of dice equal to the battling Army block’s current strength and rolls them. A single hit is scored for each die value that is BELOW the defender’s current firepower value. For example, if the Army block had a strength value of “3” and the player rolled a “1”, “2”, and “6”, the Army blocked hit twice.

Each successful hit reduces the strongest defender’s block during that initiative, wherein the owning player rotates the block to a new strength value. If the block’s strength is reduced to zero, they are removed from the mapboard and placed in the player’s Levy pool. These Army blocks can be used again, but not for the current year.

After all Army blocks have completed a single round of combat, a new round of combat begins. This continues for a maximum of 4 times. During the second, third, and fourth rounds of combat, the player can retreat the Army block on its turn instead of engaging in combat. There are a few restrictions to retreating. For example, a player cannot retreat an Army block into another contested territory or an enemy territory.

Phase 3 continues until all Army blocks that are in contested territories battle for at least 4 rounds. Then the players start the year again with phase 1, playing another card. As soon as the players have played all but their last card and combat has been concluded, winter sets in.

Winter in the Warfield

Winter represents the end of the year and the round. The players now determine if either of them have won the game and then perform a few administrative tasks.

Victory?

First, move the “Cleopatra” Army block to Alexandria. If the city is occupied by an opposing force, Cleopatra now belongs to that player

Each player now scores the value of each friendly city they currently occupy. Then players add to that number 1 victory point for each enemy leader they have killed.

If either player has 10 or more victory points, they have won the game. Pompey has a serious advantage here (starting with a larger number of victory points than Caesar), but the number of victory points earned at the end of each round fluctuates.

The Battle Continues!

If no victor has been declared, the war between Pompey and Caesar continues…

- Move all “Navis” Army blocks to a friendly port city that is within the same sea location as the block (starting with the player who is using Caesar). Any Navis not safely put in port are disbanded (sent to the Levy pool).

- Determine if each city can house the Army blocks. Each city can house 3 Army blocks, plus the number value on that city. If there are more Army blocks than the city can handle, the player decides which blocks to send to their Levy pool.

- Players can disband (send to their Levy pool) any Army blocks they like (particularly useful when you have a very weak Army block in play).

- Reset for the year and all blocks in a player’s Levy pool can be used. All the cards played are collected, shuffled with the deck, and 6 cards are dealt to each player.

To learn more about Julius Caesar, visit the game’s web page.

Final Word

The Child Geeks had difficulty learning the game. The basics of Julius Caesar are easy to grasp. Combat and movement are easy to understand, as is the use of the Command cards. Where difficulty set in was using all that in a game that kept players half blind most of the time. Several older Child Geeks tried their hand at specific strategies and sometimes that worked, but oftentimes failed. Not because they were poorly executed, but because it was the wrong strategy to use. According to one Child Geek, “I understand the basics of the game, but there are so many different ways to play your turn that it makes it difficult to feel you know what you are doing.” Only the most elite and experienced Child Geeks were able to learn the game well enough to play it competitively. According to one of these Child Geeks, “I don’t think this is a game you should teach other kids until they understand the basics of other Wargames. There’s a lot to consider when playing this game that is not easy to see.” When the votes were in, the game was given enough positive votes to save it from total rejection, but not enough for a full endorsement from the Child Geeks.

At times, Chess seemed liked an easier game to the Child Geeks…

The Parent Geeks liked the game almost immediately, but only those Parent Geeks who had played Wargames in the past and enjoyed 2-player games. The casual and non-gamer Parent Geeks stayed away from Julius Caesar, feeling rather intimidated by the blocks and sometimes complicated turns. But this is exactly what the Parent Geeks who stayed and played the game enjoyed the most. According to one such Parent Geek, “Yes! This is a great game! It’s easy to set up, allows for lots of different ways for me to play, and keeps me guessing. I love it!” Another Parent Geek said, in a much more subdued tone, “I was skeptical at first if this was a game I would enjoy playing. I found it to be a very engaging game with a great deal of tactical opportunities.” The Parent Geeks enjoyed playing the game with their peers and with their children who were ready to tackle it. The Parent Geeks voted to approve Julius Caesar.

The Gamer Geeks only disliked one thing in the game and they fixed it almost immediately. The Event cards had to go. According to one Gamer Geek, “This game is almost perfect as it is right out of the box. It’s those Event cards that ruin it a bit. Random events that hurt players? Hell no. Not after the players spend all their time tactically attempting to survive.” Another Gamer Geek said, “This game is very tactical, which is great, but I find it difficult to stay targeted on any specific strategy. I didn’t think I would like that at first, but now I do.” What it really came down to was wondering if a game that constantly asks you to act and react is as good as a game that requires you to plan and plot. Turns out the answer is yes, as the Gamer Geeks all voted to approve Julius Caesar.

The choices to be made during the game always seemed obvious to me, but the restrictions set by my Command cards made strategies difficult to plan. I spent most of my time making tactical moves, adjusting and shifting in accordance to new openings and sudden roadblocks. All good stuff with the one exception of not being able to act specifically when and where I wanted to. I had a strategy in my head the entire time, but the difficulty was in working towards it, not necessarily obtaining it. It was a different approach that, in addition to not being able to see my opponent’s blocks, made each move I made feel like a gamble. This, in turn, increased the level of anxiety and anxiousness, creating for some very intense games.

While the Parent Geeks and the Gamer Geeks enjoyed this level of intensity, the Child Geeks did not. They remained firmly rooted in attempting to make decisions based on information they knew. Again, a very good thing, but this is not that kind of game. Players have just enough information to make a choice and not necessarily a good one. In many respects, the game gives players all the rope in the world to either hang themselves out to dry or to tie up their foes. It’s what we do with that rope based on how you perceive the mapboard that ultimately leads to victory.

I could not agree more with the Gamer Geeks regarding the Event cards. I keep them when playing with new and inexperienced players, but always take them out otherwise. The Events are interesting, but their impact to the game harms the efforts of the players. And not in a good way. Random events can keep a game feeling fresh and add an edge of apprehension. Not in this case. When a player uses an Event card, the opponent almost always grumbles in disgust (or swears, if they are Gamer Geeks). Their value to the game is marginalized by the negative impact it has to the players’ tolerance of the game when in use. Any game component that makes a player think twice about playing it is seldom a good idea to keep around. The Event cards have their place in the game, but they can be removed without upsetting the game balance.

I am very pleased with Julius Caesar. It has an old school feel that made me feel nostalgic at times. But it’s also a game that feels fresh and full of energy. It’ll push you to use your tactical skills, manage your resources, maintain territory, and come to realize that a loss is not a defeat. Expect to feel exhilarated in one turn and beaten up the next. If you enjoy a challenging game that gives you all the room in the world to make mistakes and pull off outstanding victories, do play Julius Caesar.

This game was given to Father Geek as a review copy. Father Geek was not paid, bribed, wined, dined, or threatened in vain hopes of influencing this review. Such is the statuesque and legendary integrity of Father Geek.